Experts Have World Models. LLMs Have Word Models.

From Next token prediction to Next state prediction

Tickets for AIE Miami and AIE Europe are on sale now! We’ll all be there.

Discussions for this post on X and HN.

Swyx here: we put a call out for Staff Researchers and Guest Writers and Ankit’s submission immediately stood out. As we discussed on the Yi Tay 2 episode, there are 3 kinds of World Models conversations today: The first and most common are 3D video world models like Fei Fei Li’s Marble and General Intuition’s upcoming model, Google’s Genie 3 and Waymo’s World Model, 2) the Meta school of thought comprising JEPA, V-JEPA, EchoJEPA and Code World Models pursuing Platonic representation by learning projections on a common latent space.

This essay covers the third kind that is now an obvious reasoning frontier: AI capable of multiagent world models that can accurately track theory of mind, anticipate reactions, and reveal/mine for information, particularly in adversarial situations. In benchmarks, both DeepMind and ARC-AGI and Code Clash are modeling these as games, but solving adversarial reasoning is very much serious business and calls out why the age of scaling is flipping back to the age of research. Enjoy!

Ask a trial lawyer if AI could replace her and she won’t even look up from her brief. No. Ask a startup founder who’s never practiced law and he’ll tell you it’s already happening. They’re both looking at the same output.

And honestly, the founder has a point. The brief reads like a brief. The contract looks like what a contract would look like. The code runs. If you put it next to the expert’s work, most people would struggle to tell the difference.

So what is the expert seeing that everyone else isn’t? Vulnerabilities. They know exactly how an adversary will exploit the document the moment it lands on their desk.

People try to explain this disconnect away. Sometimes they blame bad prompting, sometimes they assume models being more intelligent would be able to do the job. I would wager that intelligence is the wrong axis to look at. It’s about simulation depth.

Let’s take an illustrative example about approaching people:

A simple Slack Message

You’re three weeks into a new job. You need the lead designer to review your mockups, but she’s notoriously overloaded. You ask ChatGPT to draft a Slack message.

The AI writes: “Hi Priya, when you have a moment, could you please take a look at my files and share any feedback? I’d really appreciate your perspective. No rush at all. whenever it fits your schedule. Thanks!”

Your friend who works in finance reads: “This is perfect. Polite, not pushy, respects her time. Send it.”

Your coworker who’s been there three years reads: “Don’t send that. Priya sees ‘no rush, whenever works’ and mentally files it as not urgent. It sinks below fifteen other messages with actual deadlines. She’s not ignoring you. She’s triaging, and you just told her to deprioritize you.

Also, ‘please take a look’ is vague. She doesn’t know if this is 10 minutes or 2 hours. Vague asks feel risky. She’ll avoid it.

Try: ‘Hey Priya, could I grab 15 mins before Friday? Blocked on the onboarding mockups. I’m stuck on the nav pattern. Don’t want to build the wrong thing.’ Specific problem, bounded time, clear stakes. That gets a response.”

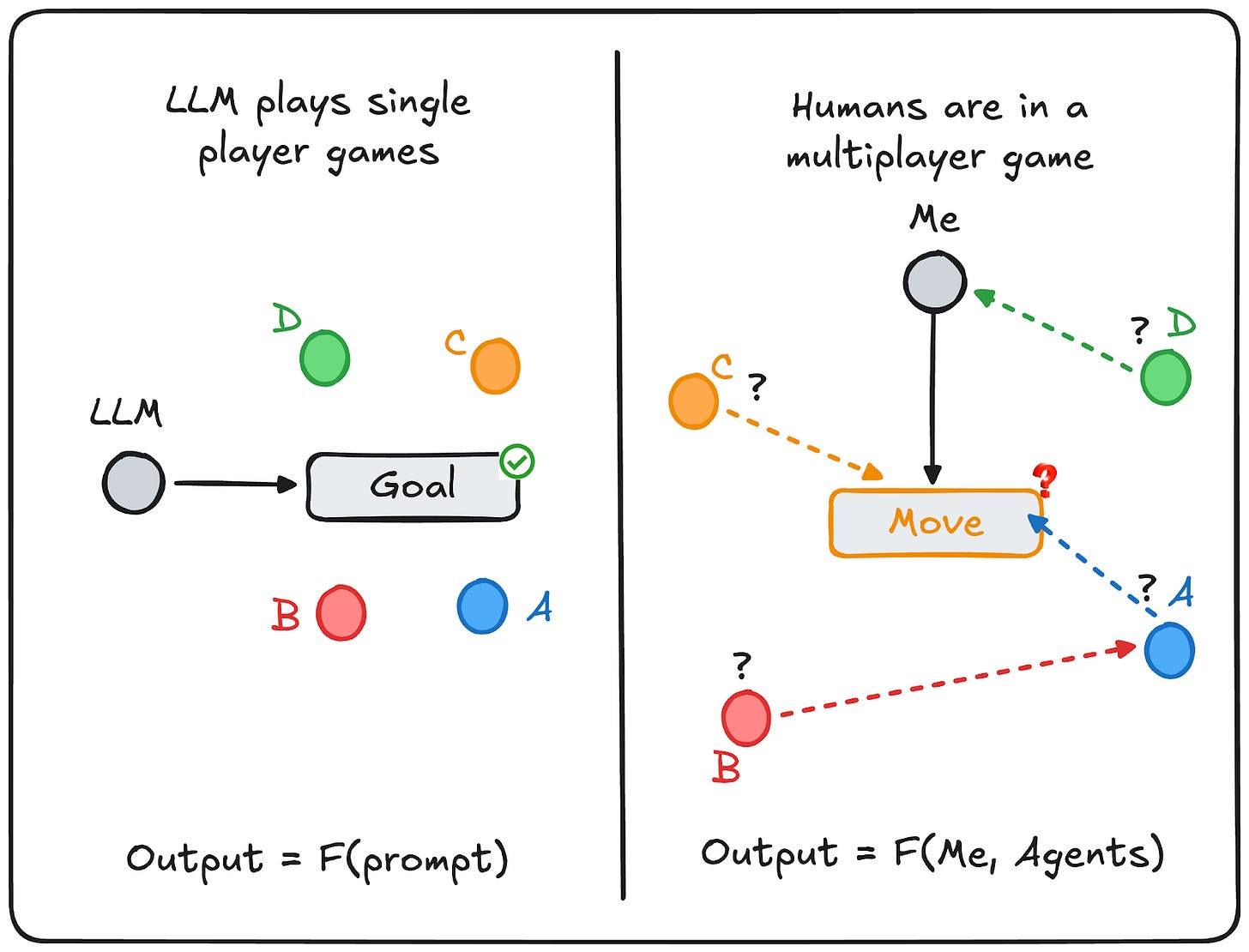

The finance friend evaluated the text in isolation. The coworker ran a simulation: Priya’s workload, her triage heuristics, what ambiguity costs, how “no rush” gets interpreted under pressure. That’s the difference. The email is evaluated by the recipient’s triage algorithm.

Adversarial Models in real world

The finance friend and the LLM made the same mistake: they evaluated the text without modelling the world it would land in. The experienced coworker evaluated it as a move landing in an environment full of agents with their own models and incentives.

This is the core difference. In business, geopolitics, finance etc, the environment fights back. Static analysis fails because the other side has self-interests and knowledge you don’t have. Pattern matching breaks when patterns shift in response to your actions. You have to simulate:

Other agents’ likely reactions (triage heuristics, emotional state).

Their hidden incentives and constraints (deadlines, politics).

How your action updates their model of you (does “no rush” mean “I’m nice” or “I’m unimportant”?).

Quant trading makes this measurable: act on a signal, others detect it, the edge decays, someone front-runs you, then someone fakes your signals to take even more money from you. The market is literally other agents modeling you back. That’s why static pattern-matching breaks: the pattern shifts specifically because you acted on it.

Once other agents are in the loop, two things start to matter: (1) they can adapt, and (2) they have private information and private incentives. The hidden state is what turns a problem from ‘just compute the best move’ into ‘manage beliefs and avoid being exploitable.’

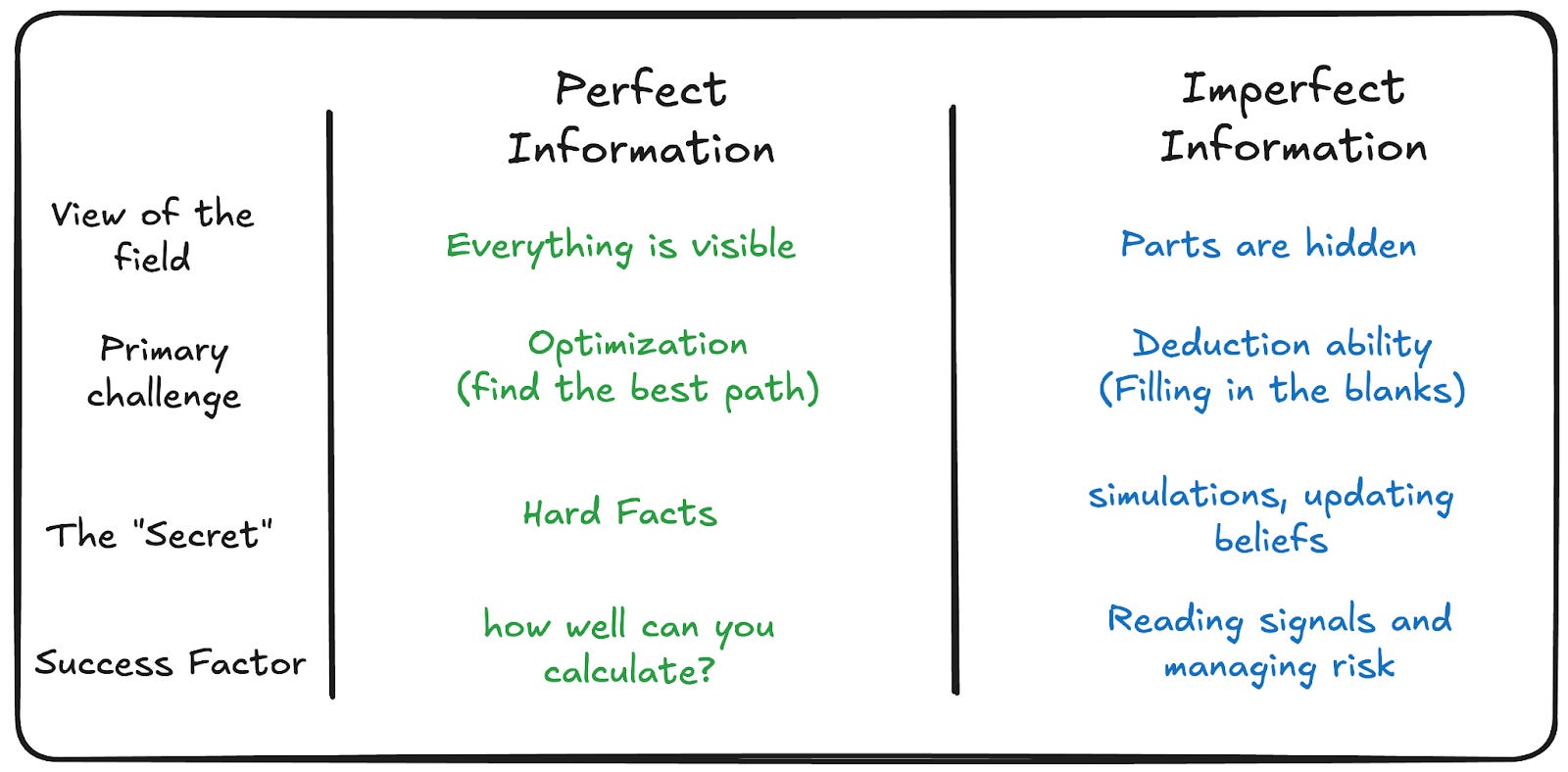

The cleanest way to see this: compare perfect-information games with imperfect-information ones.

Perfect Information Games: When You Don’t Need a Theory of Mind

Chess has two players, perfect information, and symmetric rules. Every piece is visible. Every legal move is known. There’s no hidden state, no private information, no bluffing.

You don’t need a detailed model of your opponent’s mind1 as a requirement. Yes it helps, but you need only calculate: given this board, what is the best move assuming optimal play?

Your best move does not change based on who your opponent is. Board state is board state. Same goes with Go.

AlphaGo or AlphaZero didn’t need to model human cognition. It needed to see the current state and calculate the optimal path better than any human could. The game’s homogeneity made this tractable. Both players operate under identical rules, see identical information, and optimize for the same objective. Self-play generates training signals because playing yourself is structurally equivalent to playing anyone.

When the Other Side Has Hidden State

Now, consider poker - it has the same structure on the surface. Two players, defined rules, clear objectives. But one fundamental difference: information asymmetry. You don’t know your opponent’s cards, they don’t know yours. Now, the game is no longer about calculating the optimal move from a shared state. It’s about modeling who they are, what they know, what they think you know, and what they’re doing with that asymmetry.

Bluffing exists because information is private. Reading a bluff exists because you’re modeling their model of you. The game becomes recursive: I think they think I’m weak, so they’ll bet, so I should trap.

Editor: we’re coming back into familiar territory and it may be a good time to revisit our conversation with Noam Brown on AI for imperfect information vs game-theory-optimal poker games, and what that tells us for his multi-agent work:

Scaling Test Time Compute to Multi-Agent Civilizations: Noam Brown

Every breakthrough in AI has been led by a core scaling insight — Moore’s Law gave way to Huang’s Law (silicon), Kaplan et al gave way to Hoffman et al (data), AlexNet kicked off the deep-learning an…

Pluribus: Adversarial Robustness

When Meta released Pluribus, Noam Brown made the architecture explicit:

“Regardless of which hand Pluribus is actually holding, it will first calculate how it would act with every possible hand, being careful to balance its strategy across all the hands so as to remain unpredictable to the opponent.”

Pluribus was specifically modeled so that it’s impossible to read. It calculated how it would act with every possible hand, then balanced its strategy so opponents couldn’t extract information from its behavior. Human opponents tried to model the causality (”it’s betting big, it must have a strong hand”), but Pluribus played balanced frequencies that made those “reads” statistically irrelevant. The point of the strategy was to deny its opponents consistent information.

That’s the benchmark you’re implicitly holding experts to in real life: not “does this sound good,” but “is this move robust once the other side starts adapting?”

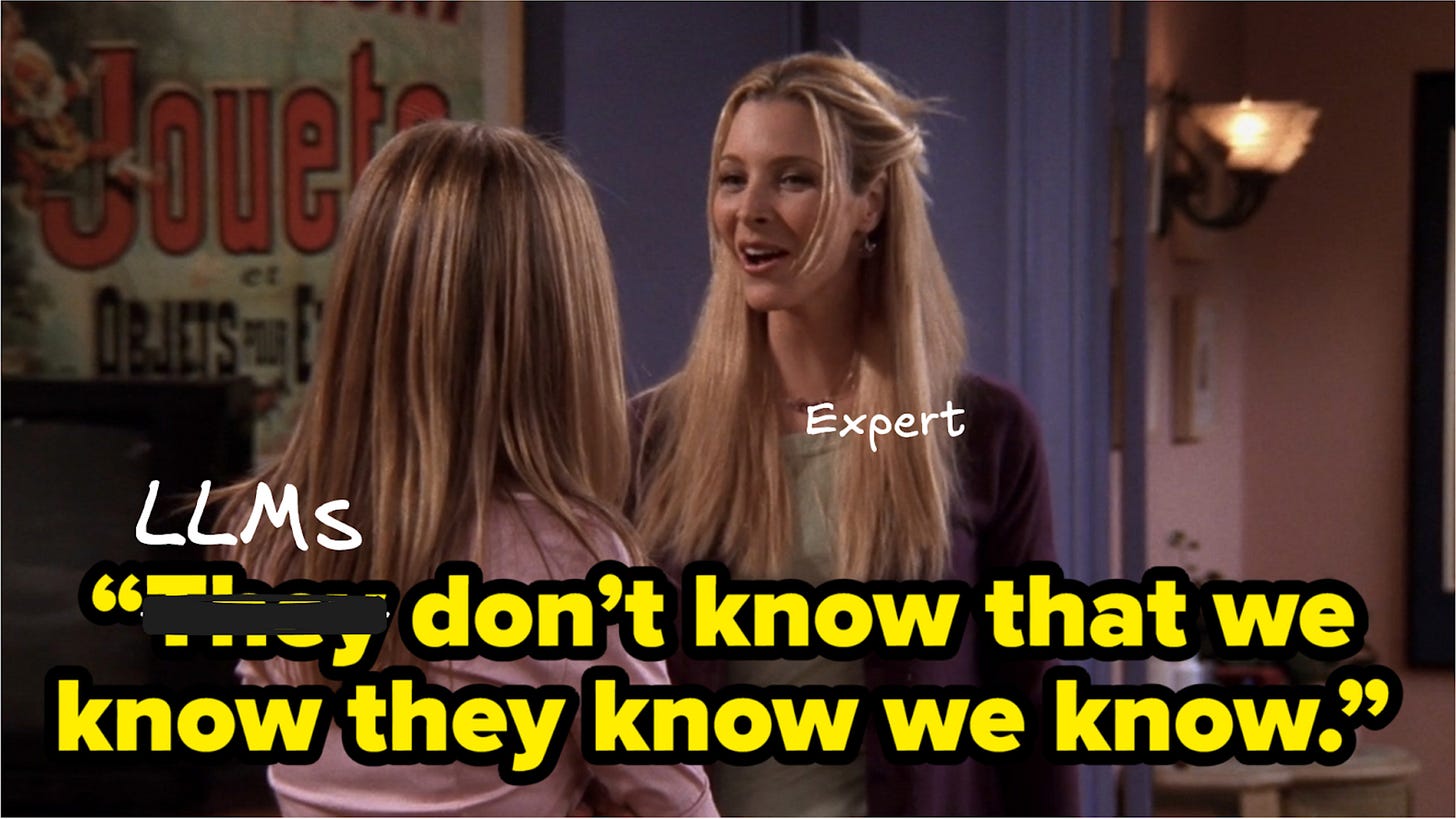

The LLM Failure Mode: They’re Graded on Artifacts, Not on Reactions

LLMs are optimized to produce a completion that a human rater approves of in isolation. RLHF (and similar human preference tuning) pushes models toward being helpful, polite, balanced, and cooperative, qualities that score well in one-shot evaluations. That’s great for lots of tasks. But it’s a bad default in adversarial settings because it systematically under-weights second-order effects: how the counterparty will interpret your message, what it signals about your leverage, and how they’ll update their strategy after reading it.

The core mismatch is the training signal compared to humans. Domain experts get trained by the environment: if your argument is predictable, it gets countered; if your concession leaks weakness, it gets exploited; if your email invites delay, it gets delayed. LLMs mostly learn from descriptions of those dynamics (text) and from static preference judgments about outputs2. Not from repeatedly taking actions in an environment where other agents adapt and punish predictability.3

Hence, the model learns to imitate “what a reasonable person would say,” not to optimize “what survives contact with a self-interested opponent?”

The obvious fix: prompt the model to be adversarial. Tell it to optimize for advantage, anticipate counters, hold firm.

This helps. But it doesn’t solve the deeper problem.

Being Modeled

Pluribus cracked what current LLMs don’t: when you’re in an adversarial environment, your opponent is watching you and updating and you have to account for that in order to win.

A human negotiator notices when the counterparty is probing. They test your reaction to an aggressive anchor. They float a deadline to see if you flinch. They ask casual questions to gauge your alternatives. Each probe updates their model of you, and they adjust accordingly.

A skilled negotiator sees the probing and recalibrates. They give misleading signals. They react unexpectedly to throw off the read. The game is recursive: I’m modeling their model of me, and adjusting to corrupt it.

An LLM given an “aggressive negotiator” prompt will execute that strategy consistently. Which means a human can probe, identify the pattern, and exploit its predictability. The LLM doesn’t observe that it’s being tested. It doesn’t notice the counterparty is running experiments4. It can’t recalibrate because it doesn’t know there’s anything to recalibrate to.

This is the asymmetry. LLMs are readable. The cooperative bias is detectable. The prompting strategy is consistent. And unlike Pluribus, they don’t adjust based on being observed.

Humans can model the LLM. The LLM can’t model being modeled. That gap is exploitable5, and no amount of “think strategically” prompting fixes it because the model doesn’t know what the adversary has already learned about it.

Why “More Intelligence” Isn’t the Fix

The natural response is: surely smarter models will figure this out. Just scale everything up? More compute on more data on more parameters in pre-train, better reasoning traces6 in post-train, longer chains of thought at test-time. But, more raw IQ doesn’t fix the missing training loop even for professionals.

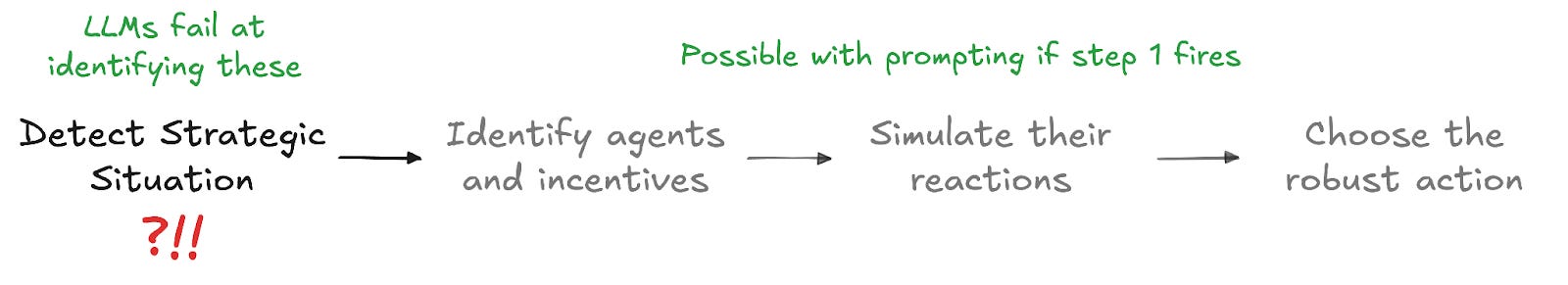

To behave adversarially robust by default, the model has to reliably do four things:

Detect that the situation is strategic (even when it’s framed as polite/cooperative)

Identify the relevant agents and what each is optimizing

Simulate how those agents interpret signals and adapt after your move

Choose an action that remains good across plausible reactions—not just the most reasonable-sounding completion

Steps 2–4 are possible with good prompting as in the example above. Step 1 is the problem. The model has no default ontology that distinguishes “cooperative task” from “task that looks cooperative but will be evaluated adversarially.”7

And even with recognition, the causal knowledge isn’t there. The model can be prompted to talk about competitive dynamics. It can produce text that sounds like adversarial reasoning. But the underlying knowledge is not in the training data. It’s in outcomes that were never written down.

The issue isn’t reasoning power. It’s the structure of the problem that is hard to define.

The Expert’s Edge

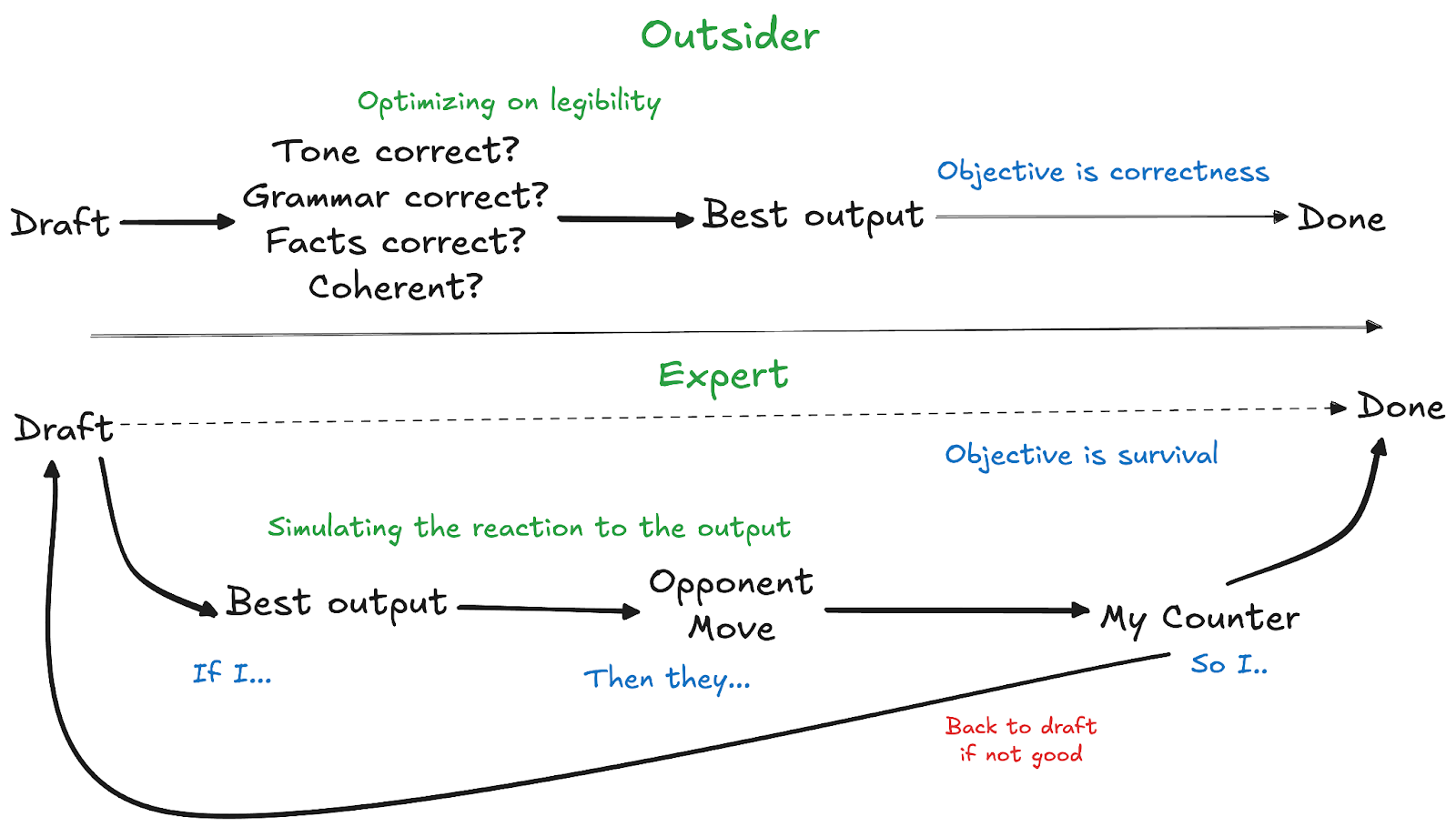

Domain experts say “AI won’t replace me” because they know that “producing coherent output” is table stakes.

The REAL job is produce output that achieves an objective in an environment where multiple agents are actively modeling and countering you.

Why do outsiders think AI can already do these jobs? They judge artifacts but not dynamics:

“This product spec is detailed.”

“This negotiation email sounds professional.”

“This mockup is clean.”

Experts evaluate any artifact by survival under pressure:

“Will this specific phrasing trigger the regulator?”

“Does this polite email accidentally concede leverage?”

“Will this mockup trigger the engineering veto path?”

“How will this specific stakeholder interpret the ambiguity?”

These are simulation-based questions. The outsider doesn’t know to ask them because they don’t have the mental model that makes them relevant.

It’s like watching Pluribus play poker and evaluating only whether the bets were “reasonable.” Of course they look reasonable. The cards it shows at showdown justify the betting pattern. But the reason Pluribus wins isn’t that its bets look reasonable. its bets are calibrated to be unexploitable across all possible opponent strategies.

The visible reasonableness is a side effect of deep adversarial modeling. And if you don’t know what to look for, you’ll never know it’s missing.

Language Data Hides the Real Skill

There’s a deeper reason LLMs are at a permanent handicap here: the thing you’re trying to learn is not fully contained in the text8. They can catch up by sheer brute force, but are far more inefficient than humans, and the debt is coming due now.

When an investor publishes a thesis, consider what is not in it:

The position sizing that limits the exposure

The timing that avoided telegraphing intent

Strategic concealment

How the thesis itself is written to not move the market against them

What they’d actually do if proved wrong tomorrow

Text is the residue of action. The real competence is the counterfactual recursive loop: what would I do if they do this? what does my move cause them to do next? what does it reveal about me? That loop is the engine of adversarial expertise, and it’s weakly revealed by corpora.

This is why models can recite game theory but still write the “nice email” that leaks leverage. They’ve learned the language of strategy more than the dynamics of strategy.

This is what domain expertise really is. Not a larger knowledge base. Not faster reasoning. It’s a high-resolution simulation of an ecosystem of agents who are all simultaneously modeling each other. And that simulation lives in heads, not in documents. The text is just the move that got documented. The theory that generated it is called skill.

LLMs dominate chess-like domains

Not every domain follows poker dynamics. You have certain fields very close to chess, and LLMs are already poised to be successful in them.

Writing code is probably the most clear example:

System is deterministic

Rules are fixed and explicit

No hidden state that matters

Correctness is objective and verifiable

No agent is actively trying to counter the model

The same “closed world” structure shows up in others: Math / Formal proofs, data transformation, translation, factual research, compliance heavy clerical work (invoice matching, reconciliation), where you can iterate towards the right move without needing a “theory of the mind”.

The important caveat is that many domains are chess-like in their technical core but become poker-like in their operational context.

Professional software engineering extends well beyond the chess-like core. Understanding ambiguous requirements means modeling what the stakeholder actually wants versus what they said. Writing good APIs means anticipating how other developers will misuse them. Code review is social: you’re modeling reviewers’ preferences and concerns. Architectural decisions account for unknown future requirements and organizational politics. That is, the parts outsiders don’t see but senior engineers spend much of their time simulating.

The parts that look like the job are chess (like). The parts that are the job are poker.

Difficulty is orthogonal to “openness” of a domain. Proving theorems is hard. Negotiating salary is easy. But theorem-proving is chess-shaped and negotiation is poker-shaped.

This is why the disconnect between experts and outsiders is domain-specific. Ask a competitive programmer if AI can solve algorithm problems, and they’ll say yes because they’ve watched it happen. Ask a litigator if AI can handle depositions, and they’ll laugh because they live in a world where every word is a move against an adversary who’s modeling them back.

The labs are starting to see this too. This week Google DeepMind announced they’re expanding their AI benchmarks beyond chess to poker and Werewolf - games that test “social deduction and calculated risk.” Their framing: “Chess is a game of perfect information. The real world is not.” The distinction isn’t novel. But it’s now officially what frontier AI research is bumping against.

The Coming Collision

As LLMs get deployed as agents in procurement, sales, negotiation, policy, security, and competitive strategy, exploitability becomes practical. A human counterparty doesn’t need to “beat the model” intellectually. They just need to push it into its default failure modes:

Aggressive opening positions, knowing the model anchors toward accommodation

Ambiguity, knowing the model resolves it charitably

Bluffs, knowing the model takes statements at face value

Probing, knowing the model won’t adapt to being read

This is Pluribus in reverse. In poker, the AI won by being unreadable. In many real deployments, the model is readable: it’s optimized to be agreeable and helpful, and its tell is that it tries to be fair.

If this sounds speculative, consider that every poker pro, every experienced negotiator, every litigator already does this instinctively. They read their counterparty. They probe for patterns. They exploit consistency. The only question is how long before they realize LLM agents are the most consistent, most readable counterparties they’ve ever faced.

Training for the next state prediction

The fix is a different training loop. We need models trained on the question humans actually optimize: what happens after my move? Grade the model on outcomes (did you get the review, did you concede leverage, did you get exploited), not on whether the message sounded reasonable.

That requires multi-agent environments where other self-interested agents react, probe, and adapt. Stop treating language generation as single-agent output objective and start treating it as action in a multi-agent game with hidden state, where exploitability is a failure mode.

Closing the Loop

The “AI can replace your job” debate often confuses artifact quality with strategic competence. Both sides are right about what they’re looking at. They’re looking at different things.

LLMs can produce outputs that look expert to outsiders because outsiders grade coherence, tone, and plausibility. Experts grade robustness in adversarial multi-agent environments with hidden state.

Years of operating in adversarial environments have trained them to automatically model counterparties, anticipate responses, and craft outputs robust to exploitation. They do it without thinking, because in their world, you can’t survive without it.

LLMs produce artifacts that look expert. They don’t yet produce moves that survive experts.

Editor: Ankit Maloo blogs at https://ankitmaloo.com/ and is working on applied RL for real world agents. Give him a follow and check out his work!

Sometimes the player against you matters only in the sense that if they can’t figure out the board, you will be punished less for risky, ambitious moves.

One of the obvious pushbacks is directly training on outcomes and not artifacts. Hard to do in training setting when you don’t know a given email is correct until after the negotiation closes.

Editor: this is clearly in RL territory. One might comment on RLVR here being still very early and not sufficiently extended beyond math, code, and artifact rubrics rather than feeding back rewards from renvironments with other actors.

The model can’t update when the adversary probes, because it doesn’t observe the probing as it happens. You can prompt it to anticipate one layer of response; you can’t prompt it to adapt mid-interaction to an opponent who’s actively modeling it.

Yes, humans are also exploitable. The problem is LLMs don’t learn from getting exploited the way humans do over a career.

Reasoning models too are solipsistic. They are not thinking about you. They aren’t thinking about the counterparty’s hidden incentives or emotional deficits. Even if prompted to “consider the opposition’s perspective,” their learning is text-based. They treat social dynamics as a causal chain of words (if “sorry” → then “forgiven”), rather than a collision of incentives. But that is to do more with training data than reasoning per se.

Editor: one difference we debated in the writing process was that I don’t see a functional difference between collaborative and adversarial situations as far as needing world models/theory of mind is concerned

Editor: at this point I’m contractually obligated to bring up Good Will Hunting and think about what Robin Williams (human) is telling Matt Damon (LLM)… except it’s not quite multiplayer or adversarial, so this is just for the footnote enjoyers like you.

the Priya example nails it. the finance friend evaluated the email in isolation. the experienced coworker simulated how it would land in Priya's inbox, against her triage heuristics, under deadline pressure

this is the gap between LLMs writing code and LLMs building systems. code that compiles isn't code that survives contact with users, adversaries, edge cases

been running production systems solo for 20 years. the best operators aren't the ones who know the most commands — they're the ones who can simulate what will break next. "if I do X, the cache invalidates, which triggers Y, which overloads Z." that's a world model

the poker vs chess analogy is perfect. hidden state + adversarial adaptation = can't just pattern match

curious where you see the fix coming from. is it more training on game theory scenarios? or do we need fundamentally different architectures to track hidden state?

This is a great framework. LLMs can regurgitate game theory but can’t yet ‘feel’ the move/counter move process. They are great at predicating the next word but perhaps not yet predicting the next emotional state. Makes me wonder if the next frontier is capturing a better understanding of human behavioral psychology and being able to relate to adversarial circumstance.

Do you think we can get there with text alone? You might make the case that art could be useful in this sense: drama, etc.

What is Shakespeare if not a picture of clashing wills.. type of the thing.